AS in many Asian cultures where the worship of semi-legendary figures is common, Myanmar has its own centuries-old tradition uniquely woven into its Buddhist fabric: the cult of nats. Buddhism may teach self-reliance and the law of causality, but for many in Myanmar, who identify themselves as Buddhists, reason alone may feel insufficient, and so quiet bargains are struck with the unseen.

As Yuval Noah Harari notes in Sapiens, humans are storytelling creatures, and it is through stories that shared memories endure. In Myanmar, tales of figures who met tragic ends, often through martyrdom or betrayal, have been etched into the nation’s memory, stirring both sympathy and affection. Devotees carve their statues, bow before them, and offer prayers: pitying the nats for their fates, yet at the same time relying on them for protection and blessings in return for devotion and offerings.

Out of centuries of yearning and lore, tragedy transfigured into ritual, and ritual into devotion, Myanmar’s cult of the nats took root.

Where the Spirits Live On

What sets Myanmar’s nat worship apart from many other folk beliefs is the richly syncretic tradition that has grown around it. Unlike many cultures where spirits are honored with simple rituals, nats are often celebrated in grand communal ceremonies with boisterous music, trance dances, and a festival-like atmosphere that blurs the boundary between ritual and revelry.While humble household shrines are the bare minimum, more devoted followers sponsor—or contribute to—special rites known as nat kana pwes (or simply nat pwes), propitiation ceremonies held at major shrines, private homes, or temporary tents. Some take their devotion further, traveling to larger communal festivals (pwe-daws), seasonally held at the nats’ places of origin or domains. Such acts of worship are often tied to vows or prior bargains with the spirits for a desired outcome. A businessman, for instance, might host a nat pwe at his home in anticipation of a lucrative deal, seeking the nat’s blessing in advance.

Whether small nat pwes or grand pwe-daws, the central figures of these rites are the nat kadaws, “consorts chosen by the nats1.” More than officiants or mediums, they are performers, taking center stage as they dance ecstatically in ritual possession: arms and hands tracing wild, unbidden arcs and loops while their feet sweep and pivot across the floor to the music of a traditional Burmese orchestra. The ensemble—clashing cymbals, resonant gongs, and piercing oboes—joins singers who perform tribute songs for the nats.

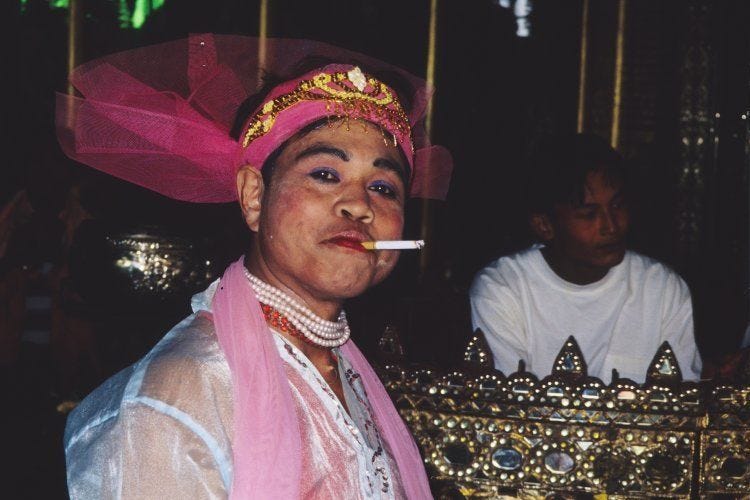

With powdered faces, glossy lips, and vivid sashes and turbans, nat kadaws channel the nats’ persona in flamboyant costumes that echo the splendor of royal dress. When embodying a spirit of the opposite sex, they often cross-dress, their movements blending the intimacy of a confidant with the poise of a court performer. The result is part theatre, part worship, alive with boisterous rhythms, soaring vocals, and a charged atmosphere.

Traditionally, the role of nat kadaw was held by women ritually “married” to a nat. Their duty was to serve as mediums and perform dances at nat pwes, but their true raison d’être as “consorts” was to attend the annual ceremonies of the specific nats they served and lead the worship there. In recent decades, however, the mantle has increasingly passed to gay and transgender men, who now share the title of ‘nat kadaws’, once reserved only for women. This shift blurs conventional boundaries of masculinity and provides a socially accepted space in Myanmar, where homosexuality remains both stigmatized and criminalized. Today, nat festivals not only offer a stage for these male nat kadaws but have become a rare space where LGBTQ devotees can express themselves freely and participate fully in ritual and revelry.

A gay medium wearing makeup and ceremonial dress at a nat pwe (Pic: Amitaba Viaggi)

WATCH: A gay nat kadaw dances, channeling a prominent female nat from Bago Region

As intermediaries, the kadaws keep alive the bond between devotees and the spirits renewing it through ritual and vows of continued devotion. Offerings are given and accepted in the throes of the dance, as if shared between old friends or kin: cheroots, bottles of toddy, plates of fried chicken, or boiled eggs, each chosen to suit the nat’s remembered tastes. For example, nat kadaws channeling Ko Gyi Kyaw, a cockfighter and drinker before his death, are often seen drinking whiskey and eating fried chicken in the height of the dance, as if keeping the spirit company over a favorite meal.

One of the distinctive features of nat propitiations is that, instead of being approached with solemn reverence or fear, nats are spoken to—through the kadaws—as if they were cherished family elders. Worshippers and spirits address each other with affectionate, familial terms such as “son,” “father,” or “grandmother”—albeit with a bit of royal bearing. Nat worship itself is understood as a family tradition, passed down like an heirloom, with the spirits watching over households for generations, much like ancestral guardians.

From Legends Comes a Pantheon

Any telling of the nats must begin with the tale of Maung Tint De, whose death is remembered as the spark that gave birth to the pantheon. A blacksmith of Tagaung, he had extraordinary strength, and it stirred fear in the king. Out of envy and suspicion, the king had him seized, bound to a magnolia tree2, and burned alive. His sister, the king’s consort, threw herself into her brother’s funeral fire out of grief and guilt at having been made a pawn in her husband’s scheme.The magnolia tree, now cursed by the spirits of the wronged pair, was cast into the Irrawaddy. The great river bore it all the way to Bagan, where it drifted ashore. Moved by a vision, the king of Bagan had the sacred wood raised from the waters, carved with their likenesses, and enshrined upon Mount Popa. From that time, Maung Tint De was no longer a man, but Min Maha Giri—the Lord of the Great Mountain—protector of Bagan. Over time, additional shrines were built atop Mount Popa for other nats, and the mountain, serving as the central sanctuary of the nat pantheon, emerged as Myanmar’s Mount Olympus.

Eventually, Anawrahta relented, allowing nat worship to continue, provided it aligned with Theravada principles. Before his reign, Myanmar’s nat pantheon included only thirty-six figures, with Maha Giri as its chief. Displeased to see an earthly spirit lead the pantheon and to ensure Buddhist oversight, he placed a prominent celestial figure from the canon—Sakka, guardian of Buddhism—above Maha Giri. This brought the total to thirty-seven, officially establishing the Thirty-Seven Nats pantheon, now anchored in a Buddhist framework through its celestial head.3

WATCH: A medium possessed by Ko Gyi Kyaw the Cockfighter

A hanging coconut in a domestic shrine for Min Maha Giri

Festivals and Rituals

Over time, nat worship blossomed into a grander, more organized tradition, unfolding as a vibrant calendar of festivals that echoes the rhythm of a seasonal fair. Like a sports league, it moves through its on- and off-seasons, and when the cycle begins, a tide of music, dance, ritual, and revelry surges across the country, drawing in believers, revelers, and traders alike. Spanning eight months of the traditional Burmese calendar—from Wagaung (July/August) to Tabaung (February/March)—the season opens with a festival honoring a young son and daughter of a Shan ruler, a Saopha.Nearby the famed Mingun Bell and Stupa, just a few miles upstream from Myanmar’s second capital city of Mandalay, lies the two siblings’ shrine. Yet Mingun was not their original home. Like Min Maha Giri, they came from the north—further upstream than Tagaung—the Irrawaddy River carrying them as its vessel. After a tragic accident in the river, their spirits drifted downstream on a great teak log until it came ashore at Mingun, where they successfully sought locals’ veneration through omens.

Today, known as the Shwe Kyun Pin Brother-Sister Nats—named after the log that bore them—their cult endures, drawing ethnic Shan and river farmers, who each year steer their fishing boats there to seek blessings for their harvests and safe passage.

WATCH: A young female medium dances in trance 4

From the Shwe Kyun Pin festival on the Irrawaddy’s western bank, the celebrations move eastward, where a small village of only 3000 residents just north of Mandalay bursts to life with its trademark nat festival—long regarded as the crowning jewel of all nat festivals. Over a week, hundreds of thousands of devotees converge on Taungbyone not only to worship the area’s nats, but to immerse themselves in the carnival-like atmosphere.

The sounds of traditional Burmese dances and operas mingle with the clamor of gambling stalls, funfairs, and liquor shops. Yet at the heart of it all are the daily nat dances, staged in opulently decorated shrines packed with devotees and onlookers, where the scents of flowers, incense, and ritual food weave together into a dizzying haze.

Every vacant space is now taken over by makeshift tents or stalls in a sprawling bazaar selling fruits, flowers, snacks, and various souvenirs. Pop-up restaurants, circuses, and theater stages line the roads, while the aisles between stalls teem with drunken revelers who shout gibberish, dance in the streets, and often break into melees.

Stories and Shrines

While each day of the Taungbyone festival features time-honored rituals, the fourth day draws the largest crowds and serves as the main highlight. On this day, the statues of the two Shwe Phyin Brothers, the “Lords of Taungbyone”, are carried on gilded palanquins in a royal-ish ceremonial procession to a pavilion within the shrine grounds for a ritual bathing. The shrine grounds also host several smaller shrines for nat kadaws not accredited to perform within the principal sanctuary where the brothers’ statues are kept—its architectural design inspired by royal halls, with multiple terraces and tiered roofs.

Devotees gather at the principal shrine at Taungbyone (Pic: Zaw Zaw/The Irrawaddy)

It’s unclear why Taungbyone draws the largest gatherings of nat kadaws and devotees every year, or why its central figures are held in such high regard. Yet the backstory carries a certain irony: it involves the staunchly anti-nat King Anawrahta. Though he sought to purge nat worship, he ultimately institutionalized a pantheon5 that included the Shwe Phyin brothers, and cemented the very tradition the festival celebrates.

According to the tale, the Shwe Phyin brothers were King Anawrahta’s favored army commanders, treated almost like his own sons6. Young and privileged, they indulged in pleasures and often bullied others. Yet their indulgence came at a great cost: distracted by revelry, they neglected the king’s sacred order that every soldier and courtier contribute a brick to a new temple under construction in Taungbyone, then a garrison town. Jealous courtiers seized the chance to mark their dereliction, leaving two brick-sized niches deliberately unfilled in the temple wall to signify it.

When the king discovered this, he casually ordered them to be caned, but the courtiers, acting out of malice, executed them instead7. In death, they became nats and pleaded the king for an official dwelling place. Moved by pity, Anawrahta had a shrine built for them beside the temple and granted them farmland nearby. The two niches in the temple’s interior wall stand quietly as symbolic scars of the brothers’ fate.8

The statues of the two brothers on their way to undergo ritual bathing (Pic: Asiantour Myanmar website)

Right after the fanfare of Taungbyone fades, another celebration begins, just to the south of Mandalay this time. Held during the same month of Wagaung in Amarapura, another royal city, the Yadanagu Nat Festival is smaller in scale but no less vibrant, and for many, just as beloved. At its heart is not a fiery warrior or vengeful spirit, but a grieving mother: Mae Wunna of Popa. Legend has it she died of heartbreak after Anawrahta conscripted her young sons, the Shwe Phyin brothers, into his army. In death, she became a nat herself, now called ‘Mother Popa’, her spirit forever linked to the lush green forests of the sacred mountain.

Unlike Taungbyone, which is rooted in venerating two ill-fated spirits, Yadanagu originated from a different impulse: to restore the spirit of the living. When a mega fire swept through Amarapura in the 19th century, the city was left broken in spirit. Wanting to restore a sense of joy and community, the queen organized a nat festival to honor Mother Popa, a motherly figure for a grieving city. What began as an act of compassion became a cherished tradition, filling the emotional void left by Taungbyone.

In the old days, almost every resident of Mandalay traveled to Yadanagu by bullock cart, turning the journey into a community picnic. Families packed their belongings and set off together, their carts winding south along the dusty road. They paused at the shady banks of Taungthaman Lake to set up temporary camps, cook meals, sing, and dance before continuing their pilgrimage to the shrine by boat. The return journeys also promised the young a romantic fanfare: while elders and unmarried women rode the slow-moving bullock carts between Mandalay and Amarapura, young single men walked alongside or trailed behind, chatting, teasing, and flirting as they went. For many, these scenes remain one of the most cherished and nostalgic parts of the festival’s past.

A ritual bathing of the statue of Mother Popa at the Yadanagu Festival (Pic: Robert Harding)

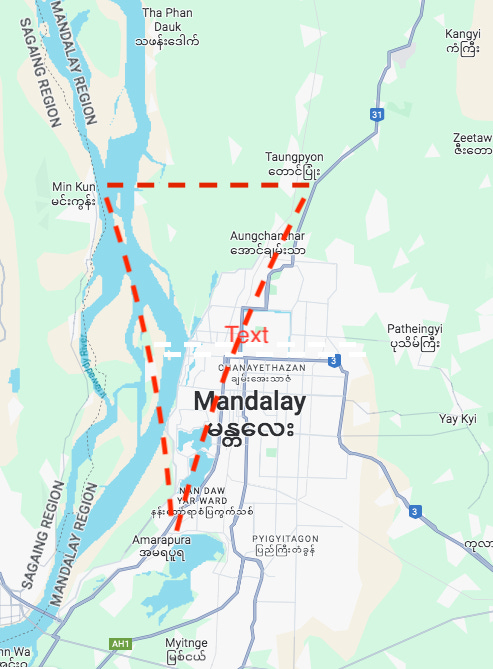

Google Maps screenshot showing the locations of the three prominent Wagaung nat festivals, marked like the points of a triangle.

The three great nat festivals unfold in the month of Wagaung along the Irrawaddy around Mandalay, each in a different place, as if together forming the three points of a spiritual triangle. Then the season continues through a succession of major and minor festivals across the country, making its way back to Mingun in Tabaung, where the final rites of the Shwe Kyun Pin nats close the cycle. Lesser-known though it may be, Shwe Kyun Pin quietly sets the rhythm of the calendar, its start and finish bound to the tale of two Shan children lost to the river yet revered ever since. Throughout the season, nat mediums, traders, and vendors alike travel from one festival to the next, while villages transform the gatherings into bustling fairs, showcasing fresh harvests, homemade delicacies, and local crafts in a whirl of trade and festivity.

While many honor a wide range of nats at private ceremonies and festivals, others turn to particular figures for specific needs, venerated solely through offerings and prayer, with no nat kadaws present and no boisterous dances involved. Agrarian communities regularly worship Pone Makyi, a figure from a Buddhist tale revered as the guardian of farmers, to secure a bountiful harvest. In the central dry zone, Kyaw Zwa, an irritable spirit blamed for prolonged droughts, is appeased through a ritual tug-of-war, during which he sits astride the rope and, once satisfied, releases the rain.

U Shin Gyi, once a hapless young boatman ritually sacrificed as a consort to the nymphs of an enchanted island, so that the vessel would be freed from being held by their magic, is worshipped by seafarers and fishers as Lord of the Sea. Shwe Nyaung Pin Grandpa, whose shrine stands just north of Yangon, draws daily visitors seeking blessings on their newly purchased vehicles. Such examples show how nat beliefs have adapted to modern life, offering protection and favor for everything from agriculture to the hazards of modern travel.

A screenshot of a YouTube clip showing a worship service for U Shin Gyi at residence

A Heritage to Be Cherished

The nat tales are only fragments of Myanmar’s vast nat lore—a treasury so rich it could rival One Thousand and One Nights. Nat beliefs have nonetheless thrived alongside centuries of Buddhism with an enduring influence. Though often associated with rural life, nat worship transcends geography and social class, with devotees ranging from farmers and shopkeepers to celebrities and politicians.The backstories of individual nats often follow a familiar pattern: tragic, untimely, or violent deaths. In the afterlife, they seek recognition or refuge from rulers and communities through dreams, omens, or other signs. Orthodox Theravadins cite this pattern to question their divine status, yet countless devotees remain devoted, whether through long-held family tradition or the human instinct to cling to the world they were raised in. For them, nat devotion can be more practically significant than formal Buddhist practice. More than symbolic, nats are omnipresent, unseen deities woven into daily life—a belief sharply at odds with Buddhism’s teaching that no being is immortal, no existence permanent.

Today, nat devotion has grown into a big industry, supported by overlapping networks of mediums, musicians, logisticians, and craftspeople. Nat festivals are vibrant gatherings that are part spiritual rite, part community fair—so entrenched that, even in the age of AI, the tradition shows no sign of fading. It remains a distinctly Burmese fusion of performance, reverence, and collective memory.

In the flicker of candles before an altar, in the swirl of music and dance at a festival, the old spirits still walk among the living, woven into the heartbeat of Myanmar.

(A short version of this piece was published in a local inflight magazine around 2008.)

‘Nat kadaw’ is commonly translated as “wife of a nat,” but ‘kadaw’ carries a more elevated sense. Historically, it referred to the wives of nobles or high-ranking officials, such as Myoza Kadaw (duchess), Min Kadaw (lady), and Bo Kadaw (wife of a British colonial officer). Even in modern usage, wives of figures who hold socially elevated roles, such as teachers, writers, and doctors, are more commonly referred to as ‘Saya Kadaw’ rather than simply ‘Saya Meinma’.

Will Boast incorrectly calls it a “jasmine tree” in Guernica’s “After the Green Death.” Botanically, jasmine (Oleaceae) and magnolia (Magnoliaceae) are unrelated. https://www.guernicamag.com/after-the-green-death/

Because the statues of these nats were enshrined on the outer walls of the Shwezigon Pagoda in Bagan, they became known as the ‘Outer Thirty-Seven.’ This distinguishes them from the ‘Inner Thirty-Seven Nats,’ celestial figures from the Buddhist Canon whose statues stand on the pagoda’s inner walls.

I surmise this captionless clip was filmed during a Shwe Kyun Pin festival, based on the lyrics in the background referring to the possessing nat as the “Saopha’s daughter” and the dancer’s features suggesting her Shan ethnicity.

Different versions of the Thirty-Seven Nats exist today. Since Anawrahta’s time, the pantheon has been revised with new figures, but many Bagan-era nats, such as Min Maha Giri, and the number thirty-seven have remained constant. It is unclear whether the Shwe Phyin Brothers were included by Anawrahta himself or appeared only in later versions.

Will Boast was likely mistaken in claiming that the Shwe Phyin brothers gained supra-natural powers by feasting on a dead alchemist’s flesh. That feat, which conferred extraordinary abilities, actually belongs to their father, Byatta, as part of his origin story. According to legend, Byatta and his brother, Byatwi, were Indian sailors whose shipwreck led them to the Mon kingdom of Thaton. There, they ate the alchemist’s remains and gained supra-natural abilities. Fearing their power, the king of Thaton had Byatwi executed, burying his body parts along the city walls as protective charms. Byatta survived, escaped to Bagan, and entered King Anawrahta’s service as Fetcher of Flowers, using his powers to pluck flowers from Mount Popa and deliver them to the palace instantly. He later fell in love with a local woman, Mae Wunna, and together they had two sons, the Shwe Phyin brothers.

Different versions of the brothers’ execution story exist. Will Boast likely encountered the most extreme, and highly implausible, variant.

Contrary to popular belief, the current shrines, temple, and site of Taungbyone’s garrison town are not original. Some researchers suggest the original locations lay further west near the Irrawaddy, with seasonal flooding and river erosion prompting the relocation of both the residential areas and the shrine. They also note that the temple near the present-day shrine was likely built later, as its architecture differs from typical Bagan-era structures.

Comments

Post a Comment